At long last, I’m going to share my Assignment Sequence. I’ve been holding back because I’ve been making changes and didn’t want to share unless I had it all figured out (ha!) But I’ve realized that’s never going to happen. So I’ll share my latest Assignment Sequence while letting you know I’ll probably change it again in the future (or maybe not, maybe I really do have it figured out this time : ). Anyway, some of my older posts (when I thought I’d have time to do a weekly update) include some details on these early assignments and exercises so feel free to look back at those. I’ll try to give enough information here so you can figure out what’s going on in my classes and replicate it in yours if you want to. You can also always reach out to me for clarification, more details, or any other reason. You can comment on the post or just email me at: steve.nelson38@yahoo.com. I’ll be at AWP in KC Feb 8-10 if you want to buy me a beer and pick my brain (or vice versa). Here is the information for the panel I’ll be part of:

Title: Beyond Composition: Creative Action in First-Year Writing Courses

Number: F204

Date/Time: 1:45pm – 3:00pm on Friday February 9, 2024

Location: Room 2215A, Kansas City Convention Center, Street Level

Okay, so this will cover the first 6 weeks of composition class (this is for a 15-week semester and a class that meets twice a week) (and this is the only composition class these studnets are required to take). First, I’ll provide the weekly calendar then below that details on the assignments and exercises (in the order they will be completed). For my grading, exercises are worth 10 points each and assignments (papers) are worth 100 points each.

FYC Class Calendar Weeks 1-6

Week 1:

T: Introduction to ENG 104, Exercise 1 (Introductory Letter) written in class

R: Exercise 2 (What is Good Writing?) completed in class,

Week 2:

T: Assignment 1 (Photo Essay) due, Exercise 3 written in class, Introduction to Assignment 2 and “Self-Reliance” (we read and discuss pargraph 1 and watch 1 or 2 videos to introduce students to Emerson and “Self-Reliance”)

R: Exercise 4 (quotations, paraphrases and thesis statements) completed in class, Exercise 5 (Sentence Outline) completed in class

Week 3:

T: Exercise 6: (Discussion of Quotes from “Self-Reliance” + Planning Outline for Assignment 2) written in class (students needs to finish reading “Self-Reliance” before class meets and choose 2 quotes for class discussion)(arrange the chairs so students can all see each other for this class session if possible)

R: Exercise 7 completed in class (review and discussion of sample papers), Explain Exercise 8 (examples of “good” and “bad” writing)

Week 4:

T: Draft of Assignment 2 due for Peer Review (Exercise 9) (students bring 4 copies to class),

R: Exercise 10 (Show, don’t Tell) completed in class, Exercise 11 (Rhetorical Analysis) completed in class

Week 5:

T Assignment 2 due for grade, Exercise 12 completed in class (Academic Conversation on “Grit”), Present Assignment 3

R: Exercise 13: Introduction to Logical Fallacies

Week 6:

T: Draft of Assignment 3 (letter to Emerson) due (students bring 4 copies to class), Exercise 14 (peer review) completed in class

R: Individual Conferences: Check in and review Assignments 1, 2, and 3 (1 and 2 should be graded already). Depending on your schedule and the number of students, this may take up another class period in Week 7)

So that is the plan, here are the assignment sheets and explanations for everything:

Exercise 1: After I show students an introductory PowerPoint outlining why learning to write is important, stating my goals for the class (what I hope they will learn), and introducing them to the “Rhetorical Situation” I want them to consider for everything they write, I ask them to write me an Introductory Letter, answering these questions:

Dear Professor Nelson……

Q1: What are your goals for this class?

Q2: How do you feel about writing? (please be honest and if you are not a fan of writing, tell me so and tell me why)

Q3: What are some good writing/English class experiences you have had. Describe them. What made them good?

Q4: What are some bad writing/English class experiences you have had. Describe them. What made them bad?

Q5: What do you like to read?

Q6: What is the best thing you have ever written? This could be a paper for class, a short story or poem, a love letter, break-up letter (or email or text), a prayer or journal entry, et cetera.

Q7: Highlights from your break (winter or summer)?

Q8: What else should I know about you as a student or writer?

Thanks in advance for answering these questions thoughtfully and thoroughly. Your responses will help make ENG 104 better for all of us.

Exercise 2: What is “Good Writing?”

First, I ask students to freewrite 8-9 minutes answering the question, “What is Good Writing?” Then I ask students to share some of what they wrote, writing their responses on the board, and briefly discussing these responses. Then I break the class into groups, and give them this task:

Your group’s objective is to come up with one dictionary style definition of “good writing” (this should be a universal definition that can apply to novels, essays, instruction manuals, et cetera)

Here are some examples of definitions:

mammal: a warm-blooded vertebrate animal of a class that is distinguished by the possession of hair or fur, the secretion of milk by females for the nourishment of the young, and (typically) the birth of live young.

language: the principal method of human communication, consisting of words used in a structured and conventional way and conveyed by speech, writing, or gesture.

You don’t have to point out that they are mammals using language, but some students will appreciate the choice of examples.

Let the groups work a while on their own then go around the room and check their definitions, making suggestions as needed. No groups will come up with the perfect definition and that’s okay. Once they have a definition they are satisfied with, either have one member of the group write it on the board or have one student email it to you (and you can use the projector to share them with the class). (10-15 minutes)

Once all definitions are available for viewing, have one group member read it aloud and then you can respond (or ask students questions) and discuss the strengths and flaws of the definition. (10 minutes)

At the end of the session, collect all the definitions (paper copies or email) and tell students you will work on combining the best of all the definitions to come up with a strong definition of “good writing” you all agree on and can use for the rest of the semester and you’ll bring it to an upcoming class session.

This is a good way to get students working in groups, with a specific task. You can complete this in a 50-minute class. Along the way, you will learn more about what they value, or what they’ve been taught to value, in writing (and what you have to teach and maybe unteach them). You get to model the thinking/writing/revision process that you want students to engage in all semester. This also helps (as other early-semester assignments do) that this is “their” class, not just yours. Specifically, this exercise lets them feel like they have come up with a definition of good writing (they are, but with your help) and later in the semester, you and they can both refer back to this for every assignment to help determine if they are producing and submitting “good writing.”

Assignment 1: Photo Essay

For this exercise, choose a recent photo of yourself and write a short essay telling the story behind the picture. Your objective is to write expansively on the moment of the photo, making it as interesting as possible. You may tell your reader what was going on in your mind at the time (consciously and otherwise), where have you just come from, where are you going, who is with you in the picture, who took the picture, why is this an important moment in your life, et cetera.

As you tell the story, you should also try to bring the scene to life by describing the physical setting of the photo, using a variety of sensory details (sight, sound, smell, taste, touch). The most effective way to bring the scene to life for your reader is to SHOW, not just TELL what is going on (for example, instead of saying “It was very hot” try something like “I could feel the sweat dripping down my back”).

Keep in mind that your reader needs to be provided with all necessary background information (who, what, where, when, why, and how) to make sense of the story you tell.

After reading the essay, readers should have a good sense of the experience you are describing, understand why it was important for you, and feel like they know you a little better (your personality, history, interests, likes and dislikes, etc.)

Write this essay in first-person point of view (I….).

Your essay must be typed and double-spaced. Aim for at least 2 pages. Aim well. Bring a copy of your photo on a separate sheet of paper. These photos will be used for an in-class writing exercise so please bring a photo you are comfortable sharing with the class.

Rhetorical Situation:

Your authorial voice: You, the subject of the photo, who wants to tell the story behind the experience captured in the photo

The content: A detailed, description of the experience captured in the photo

Your audience/reader: Someone who is interested in reading about your experience but has no prior knowledge of who you are, what the experience was, when you had this experience, who you were with, et cetera

Your objective: Your goal is to bring this experience to life for your reader in an engaging way, so your reader understands your experience and remembers it clearly after reading your essay.

This should be a fun assignment for the students. The keys are that the essays need to be descriptive, include lots of specific details, and provide all necessary background information (taking the readers’ needs into consideration–so anticipate making comments along these lines when you grade the papers). I have found this to be a great way to get students writing and learn a little bit more about them. It’s also provides great material for an in-class exercise (details in Exercise 3).

Exercise 3: In-class creative writing exercise

Students should have completed Assignment 1 and brought the photo the essay was based on to class. Here are the instructions for students:

For this activity, you will exchange photos (just pass them around the room so you do not have the photo of the person sitting next to you or someone you already know). For 8 minutes (per photo—we will do this 3 times), you are going to describe the story of the photo just as you did with your own for the Photo Essay you wrote for today’s class. The difference, of course, is that for today’s exercise you do not know the story behind the picture and need to create it. So begin by looking at the details of the photo and then you can either: 1) try to imagine/guess as accurately as possible what really was going on when the photo was taken or 2) be as creative as you want to be and come up with a story (as crazy or farfetched as you want it to be). The only rule for this exercise is to keep writing for the full 8 minutes (until I tell you to stop) (I will let you know when there are 2 minutes left) and, as you did with your Photo Essay, be specific, use as many sensory details as possible, Show, don’t Tell, and try to keep your reader as engaged as possible by making the story interesting. This should be written in first-person POV (I……). So for 8 minutes, leave you identity behind and take on the identity of the person in the photo. Have fun!

Note to Instructors: This is a fun class session where students get to do some creative writing and also get to know each other a little better. The first thing I do is make sure that if there is more than one person in the photo, students identify themselves (draw an arrow pointing to themselves). For the distribution of the photos, just make sure they are not writing about the person sitting next to them. After all 3 8-minute (or 10 if you’ve got the time) writing sessions, ask students to return the photos to their owners, then ask for volunteers—either students can volunteer to read what they wrote in class about a specific photo or they can volunteer their photo and hear what others wrote about it (to encourage volunteers, I tell them this is the only way they’ll find out what others have written). If there are not enough volunteers, you can choose photos that look interesting/you want to hear about. Whichever way it is decided, there should be 3 readers for each photo (identify them all before the reading begins) and after these students read what they have written in class, ask the subject of the photo to briefly explain the real story behind the photo (I used to have students read the essays but it takes too long—it’s better to cover more photos (ideally with different readers).

I’ll also present Assignment 2 on this day at the end of class. Here’s the Assignment Sheet:

Assignment 2: Summary of “Self-Reliance”

A summary is a condensed version of another author’s text. You provide a summary to present another author’s ideas to your reader. When presenting the ideas from your source, do so objectively (don’t agree or disagree or comment on the text or present your own examples to help explain it—just tell your reader what the source writer is saying). You will need to do this often in both your academic writing and in your career.

Your summary should be a combination of paraphrase and direct quotations. A paraphrase is the source writer’s ideas in your own words. A quote is a word-for-word presentation of the other writer’s words. Use quotes to emphasize the most important parts of the work you are summarizing or when you don’t believe you can accurately convey the ideas in your words.

For this assignment, aim for 3+ pages and include 6-8 short quotations.

When you present quotes, use a signal phrase as in:

Emerson says, “Envy is ignorance” (2). (the underlined portion is the signal phrase (use present tense for MLA format)).

When you are paraphrasing Emerson (presenting his ideas in your own words) do not present more than two words in a row from the essay without using quotes or this is a form of plagiarism.

Keep in mind your goal is to accurately sum up Emerson’s argument, writing as if your reader has not read “Self-Reliance.” To provide a good summary, answer the following questions (though you do not need to limit yourself to these):

- How does Emerson define self-reliance?

- According to Emerson, why is it difficult to be self-reliant?

- What are the benefits of being self-reliant?

- What are the negative consequences of not being self-reliant?

“Self-Reliance” was not written in academic form, with a thesis statement, but for your summary, you need to write a “thesis statement” for “Self-Reliance.” This should come at the end of the first paragraph of your summary (the end of the introduction, which can be brief for this paper). You may not know what the thesis statement/argument is until you have written a draft of the summary but it should look something like an answer to these 4 questions, something like this:

According to Emerson “Self-Reliance” is…. It is difficult to be self-reliant because….. However, the benefits of being self-reliant are….and those who are not self-reliant…….

As you can see, a well-developed thesis statement may be made up of multiple sentences. Your thesis statement should also preview the order/organization of subtopics/ideas in the paper.

As you read, be sure to take notes, which may include questions, comments, observations, and definitions of words you’ve looked up. This is a challenging essay so please plan your time accordingly.

Also, though you are only writing a summary for this assignment, not responding to Emerson’s argument, we will do that in upcoming class discussions and you will write about your responses in a later assignment, so keep those in mind and take notes for yourself as you read (for example, do you agree with Emerson’s argument? Disagree? Why? How do his ideas relate to your life and society today?).

Rhetorical Situation

Your authorial voice: You are familiar with the source you are summarizing (in this case, you have read “Self-Reliance” and thought about Emerson’s argument) and you are presenting it objectively (not responding to the argument) (when writing a summary, think of yourself as acting like a channel through which the original source is being heard).

The content: A condensed version of the argument the source presents, with some quotes highlighting key points from the source.

Your audience/reader: Someone who is not familiar with the source (in this case, someone who has not read “Self-Reliance.”)

Your objective: Your goal is to explain the main argument/key ideas of the source to your reader. After reading your summary, your reader should have a good idea what the key points of Emerson’s argument are.

Exercise 4: Quotation, paraphrase, and thesis statements

The first part of this exercise is designed to show students how I want them to present quotations and paraphrases for Assignment 2 (and throughout the semester). The second part is to introduce them to thesis statements (I’ve included then Thesis Statement handout as well)

- Present a direct quote from paragraph 1 of “Self-Reliance.” Do this in three parts: introduce the quote (be sure to identify the author in a signal phrase), present the quote (and page #), then respond to/explain the quote.

- Paraphrase (restate in your own words) the following passage from page 2 of “Self-Reliance”:

“There is a time in every man’s education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better, for worse, as his portion; that though the wide universe is full of good, no kernel of nourishing corn can come to him but through his toil bestowed on that plot of ground which is given to him to till.”

- Write a thesis statement in response to one of the questions below. In your thesis statement, first present the counterargument, then provide at least 3 reasons supporting your position:

For example, a thesis statement in response to the question: Should a writing class be required for all first-year college students? may be:

“While some may argue that college students get enough writing practice in their other classes, a writing class should be required for all students because it will help them develop an efficient writing process, they will learn the value of revision, and let’s face it, students have loads of fun in these classes.”

Should people be allowed to keep pit bulls as pets? Why/why not?

Should motorcycle riders be required to wear helmets? Why/why not?

Should college students be Facebook friends with their parents? Why/why not?

Should grade-school children have daily homework?

Which sport is the toughest to compete in?

Should a literature class be required for all college students?

It is better to have loved and lost than never loved at all?

Exercise 5: Sentence Outline

For today’s in-class group exercise, you will create a sentence outline/reverse outline for the article “The future of writing is the future of thinking!” The purpose of this is to help you see the specific points a paper makes and see how these ideas are organized. You will do this with some of your assignments later in the semester (and it is also a helpful tool for reading comprehension)

After reading the full essay, go back through the essay, paragraph by paragraph, and write out that main point for each in one complete sentence.

The article I’ve been using for this is “The future of writing is the future of thinking!” by Anand Tamboli (I shorten the paragraphs to make it twelve). But you can use any short, relevant reading for this exercise.

Exercise 6: Pre-Writing Outline for Assignment 2

I’m using this exercise for the first time this semester and it has helped improve students’ drafts of Assignment 2. It feels a little prescriptive but this assignment is a summary with very clear objectives (and don’r worry, some students will still not submit a draft with a good thesis and/or quotes in the right place). I print this on both sides of a paper and check them (this day if there is time or at the start of the next class while students are working on Exercise 7.).

4-part thesis statement for Assignment 2:

Emerson defines self-reliance as:

He says it is difficult to be self-reliant because:

The benefits of being self-reliant are:

The negative consequences for not being self-reliant are:

Quotes that support Point #1:

Quotes that support Point #2:

Quotes that support Point #3:

Quotes that support Point #4:

Exercise 7: Practice Peer Review for Assignment 2

For this exercise, I give students’ papers from previous semesters—ideally one that has a number of issues (mistakes I don’t want students to make) and one that is better. We read the papers aloud (one paragraph at a time) then I have the students work in groups writing out the peer review sheet and then we discuss the papers and their comments as a class.

Here are the instructions I give them and the questions on the peer review sheet (which will also be the sheet I use to grade their papers):

In addition to providing comments on the paper you are reviewing, answer each question with 2-3 complete, well-developed sentences. Do not use the words/phrases from the question in your answers. For example, for question 1, do not simply say “the intro introduced the topic and engaged me as a reader”. Instead, refer to the specific ideas in the paper you are reviewing and/or explain why you are answering the question as you are.

Grading Rubric Assignment 2

Does the introduction introduce the topic and engage the reader?

Does the paper have a clear, well-developed thesis statement that presents Emerson’s argument and accurately previews the organization of the paper?

How well does the paper present Emerson’s argument? Would a reader who has not read “Self-Reliance” understand Emerson’s main points? Does the paper provide enough specific details and explain key ideas from “Self-Reliance” clearly and thoroughly?

Does the paper include relevant quotes that help make Emerson’s argument clear to the reader? Are the quotes introduced properly? Are there enough quotes? Too many? Too few? Does the writer explain the quotes for the reader’s benefit?

Is the paper well organized? Are paragraphs appropriate lengths and do they focus on different subtopics from the essay? Does each subtopic relate to the thesis? Do paragraphs begin with topic sentences? Are transitions between paragraphs (and ideas) smooth?

Rate the paper’s grammar, clarity, and readability:

Needs improvement (lots of mistakes and confusing sentences

Developing (readable, but needs substantial improvements

Proficient (only minor revisions needed)

Advanced (a pleasure to read and I couldn’t find any errors)

Does the paper stay focused on objectively presenting Emerson’s argument (which means not agreeing or disagreeing and not presenting ideas or information that is not in “Self-Reliance”)?

Does this paper have a conclusion that sums up the main points, restates the thesis statement, and leaves a lasting impression?

Other comments or suggestions for revision:

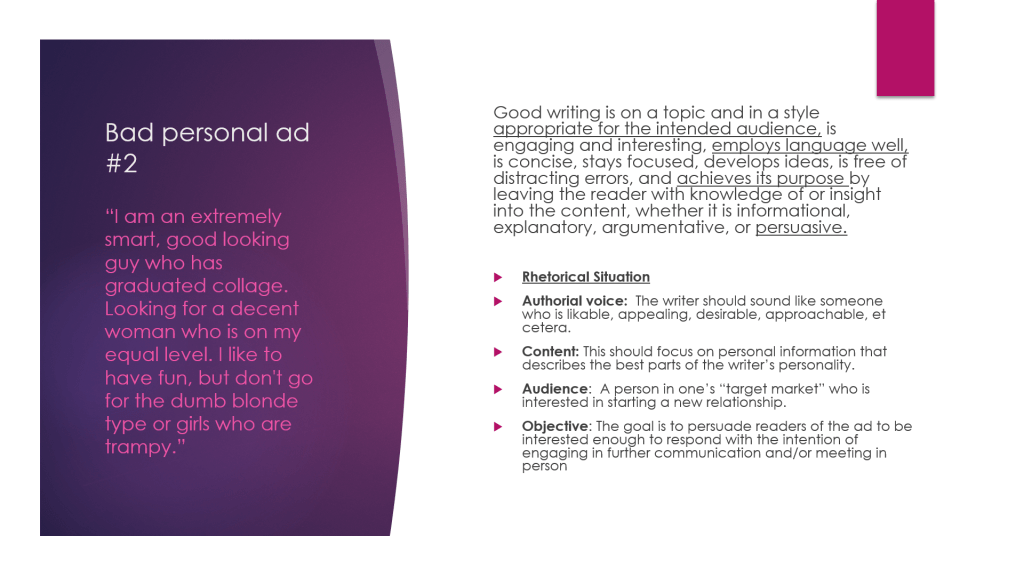

Exercise 8: Examples of “Good” and “Bad” writing

First, I give the class our “class definition” of good writing, which is something like this:

“Good writing” is on a topic and in a style appropriate for the intended audience, is engaging and interesting, employs language well, is concise, stays focused, develops ideas, is free of distracting errors, and achieves its purpose by leaving the reader with knowledge of or insight into the content, whether it is informational, explanatory, argumentative, or persuasive.

Then I ask them (any time over the course of the semester)to submit at least 3 examples of good or bad writing with a brief explanation. I present a “What is Good Writing?” PowerPoint (this is described in more detail in an earlier post) with the defintion of “good writing” and some examples of bad writing (some funny personal ads I found) and one example of good writing (“Escape” (the Pina Colada Song) by Rupert Holmes. I time it to show a video of Holmes singing the song at the end of class (it’s a great way to send them out). Did you know Holmes is now a best-selling, award-winning author??

Exercise 9: Peer Review of Assignment 2.

Students bring 4 copies of their rough drafts to class, I collect them all, then break students into groups (ideally 3) and give them a paper to read and give feedback on (same questions as Exercise 7). When groups are done, I go to the group and review the peer review sheet to make sure it is complete and will be helpful for the writer. While students are working, I’ll read over the openings of all the papers to review the thesis statements (and more if there is time). One challenge of this exercise is keeping all the papers organized and with the proper peer review sheets (so ask students to write some identifying info on the peer review sheet–title, student’s name (if it’s there though I tell them they do not need to include their names on the drafts), or the opening sentence).

Exercise 10: SHOW, don’t TELL exercise with Benjamin Franklin quotes

Below are a number of Benjamin Franklin’s famous aphorisms (an aphorism is a terse saying embodying a general truth or observation). To make sense of these, you must think about the quotations before the full meanings become clear.

For today’s exercise, each group will select two of the quotes. First, think about the quote then write in your own words what you think Franklin means (this is TELL-ing your reader what it means). Secondly, provide a real-life (actual, not hypothetical) example that SHOWS (not just tells) what the quote means. You must write in complete, grammatically correct sentences.

For example: “When the well’s dry, you know the worth of water.”

- This means that people don’t appreciate what they have until they don’t have it anymore (or need it).

- For example, “I didn’t realize how valuable the peer review process was until I had to write a paper for my History class. I made a number of mistakes in my paper but didn’t realize it until it was graded. I got only a 68 and it was too late to do anything about it.”

Choose 2 of these:

“He that lives on hope will die fasting.”

“Do you love life? Then do not squander time, for that’s the stuff life is made of.”

“Sloth, like rust, consumes faster than labor wears; while the used key is always bright.”

“If Jack’s in love, he’s no judge of Jill’s beauty.”

“Genius without education is like silver in the mine.”

“Time enough! Always proves too little.”

“Diligence is the mother of good luck.”

“’Tis easier to surpress the first desire than to satisfy all that follow it.”

“Employ thy time well if thou mean to enjoy leisure.”

“We may give advice, but we cannot give conduct.”

Exercise 11: Rhetorical Analysis

For this exercise, first give brief explanation of ethos, pathos, and logos. Then the class should read a short essay or article to analyze. I’m including the handout I give to groups. After all groups are done, we discuss this as a class.

What is the writer’s main point/thesis/argument? (write a thesis statement (position + reasons) for this article)

Who is the intended audience? Why do you believe this is the intended audience?

What is the writer’s objective/how does the writer want readers to respond?

For all of the following, discuss and be prepared to explain why the examples you list are examples of ethos, pathos (identify the specific emotion being activated) and logos.

Ethos example #1:

Ethos example #2:

Ethos example #3:

Pathos example #1:

Pathos example #2:

Pathos example #3:

Logos example #1:

Logos example #2:

Logos example #3:

Finally discuss the effectiveness of the writer’s use of these techniques, making references back to examples you have presented and explain why they are or are not effective. Which technique did the writer use most effectively? Least effectively?

Exercise 12: Academic Conversation on “Grit”

This is intended to be an introduction to an Academic Converstation. We watch Angela Duckworth’s famous TED Talk on “Grit” and I pass out 5 different articles (1 per group), each responding to Duckworth’s TED Talk in a different way. This exercise can be completed on a different theme (with different readings) that better match your course theme.

Here’s the handout I give students:

For today’s in-class exercise, we will watch Angela Duckworth’s TED Talk“Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance.” Then, in groups, you will look at some other articles and studies that “joined the conversation” about Grit (similar to what you will do for your upcoming Research Paper). We’ll discuss the content/arguments of these articles, come up with thesis statements for them, and share these with the class. We will also discuss the strength and/or weaknesses of the arguments, and (if time allows) engage in Rhetorical Analyses of the arguments.

By the end of today’s class, you should have an introductory understanding of Duckworth’s argument about “Grit” (and see why others say it is/is not the key to success), get an idea of what an “academic conversation” looks like, and further develop your undestanding of Rhetorical Analysis.

After everyone in your group has read your group’s article, answer these questions:

What is the writer’s main point/thesis/argument? (write a thesis statement (position + reasons) for this article). In what ways does this agree/disagree with Duckworth’s argument in her TED Talk?

Assignment 3: Personal Letter to Ralph Waldo Emerson

I make sure my students remain objective in Assignment 2 and don’t respond to Emerson’s ideas in “Self-Reliance” (though they do when we discuss the essay in class). Then for this assignment, they must respond and make connections between Emerson’s ideas and their own lives and the lives of those around them. I have them write this in a letter, which allows them to be less formal and more creative and also adds a new set of challenges for them as writers because they have to explain contemporary society to Emerson (who for the purposes of this assignment, is still living in the 1840’s). Here is the assignment sheet:

Assignment 3: Now that you have read “Self-Reliance” and written a summary, I’m going to ask you to think and write about some of Emerson’s ideas in a different way—a 3-4 page letter to Emerson.

For this letter, imagine Emerson is back in 1841 and you are writing to him from the present (2024, obviously) and letting him know how people in society today are doing in terms of being self-reliant, avoiding conformity, thinking for themselves, living in the present, et cetera (all the things he is trying to motivate readers to do in his essay).

A key for this assignment is to be specific when you explain contemporary society to Emerson (you can call him Ralph for this assignment if you want to) because he won’t know what Facebook, snapchat, TikTok, and even television are (you don’t have to go too far explaining how the technology works but make it clear that this sort of communication is now readily available and very popular). Remember to SHOW, not just TELL Emerson what life is like in 2024.

You can talk about social media, politics, religion, education, or whatever else comes to mind. Do you think Emerson would be happy with the way people are living their lives? In the battle between self-reliance and conformity, which side is winning? What have you found to be the key influences in promotion of both self-reliance and conformity (education, religion, friendships, social media, family, etc.)

You can also reflect on and discuss your own behaviors, attitudes, choices, et cetera as they relate to self-reliance and conformity? Would Emerson approve of the way you are leading your life?

I hope that framing this as an informal letter will be a fun assignment for you and lead you to some new ideas about “Self-Reliance” and how Emerson’s ideas relate to our lives in society today and your life in particular. Aim for 3-4 pages (but if you have more to say, keep writing because Emerson love to read!).

However, I do want you to end your opening paragraph with a thesis statement that sums up your argument/previews the subtopics you will discuss in your letter. For example: Ralph, the key things I want you to know about how people are living in 2024 are…….

For this assignment, my advice is to write a draft of the letter first, using the act of writing to discover what you want to say to Emerson, then go back and identify the subtopics/main points you have made in the letter, then write a thesis statement, going back and revising/reorganizing the letter to match the thesis as needed.

Rhetorical Situation

Your authorial voice: You are a college student in 2024 writing about your own personal and unique perspectives on your life and the ways others are operating in society today in terms of being self-reliant and/or conformist.

The content: A detailed description and analysis of how people are operating in society today in terms of being self-reliant and/or conformist, with specific examples that SHOW how people are/are not being self-reliant and maybe how this is affecting them (for better or worse).

Your audience/reader: It’s Ralph Waldo Emerson, sitting at home in 1841, with no idea what’s coming in your letter.

Your objective: Your goal is to explain to Emerson how people think and act today in terms of being self-reliant. You want to explain to him what society is like in 2024 (different in many ways than it was in 1841 but also similar in other ways) and let him know whether or not his pleas about the importance of self-reliance captured in his essay were heard and followed, or not. Let him know if he would be proud of the way people act and think today, or not.

Exercise 13: Introduction to Logical Fallacies

For this exercise, we first watch a video on logical fallacies (there are lots of good ones) and I give them this handout (the fallacies we’ll focus on) and ask them (in groups) to identify the fallacy in the statements. I collect these and check them, giving them back to students as many times as possible (sometimes over the course of weeks) until they have identified them all correctly. Here is the handout:

Below is a list of logical fallacies followed by a list of fallacious statements. Your group needs to identify the fallacy being committed in each.

Bandwagon appeals: Urging the audience to go along with the crowd and/or the popular choice.

Red Herring: Introducing an irrelevant topic into an argument to divert the attention of listeners or readers from the original issue

Circular Reasoning: Trying to support an argument by simply restating it in other words.

Straw man: Setting up a weak counterargument that can be easily attacked.

Tu Quogue: Saying someone shouldn’t be listened to because he or she has done the thing he or she is arguing against.

Appeal to Ignorance: Telling people to accept a conclusion because there is no definitive proof for either side of the argument.

Appeal to Authority: Trying to convince the audience by referring to or getting a testimonial from a famous person (who is not an authority on the subject).

False Dichotomy/ Either-Or: Arguing that only two alternatives are possible, even though the argument is more complex than that.

Slippery slope: Contending that if an event occurs, it will set in motion a chain of events that will lead to something much worse happening.

Ad hominem: Making a personal attack rather than addressing the position being argued.

Hasty generalization: Jumping to conclusions without sufficient evidence and/or relying on stereotypes to assess individuals.

Begging the question: Presenting an argument as true without any support or evidence to support it.

Faulty analogy: Making a comparison that does not hold up to the argument it is supporting.

The Relativist Fallacy: Claiming that something is true for most people is not true for a particular person.

Non-Sequister/Missing the Point: Moving an argument in a nonsensical direction or reaching the wrong conclusion.

Complex Question Fallacy: Posing a question which implies something that has not been proven.

Appeal to Emotion: Trying to get people to accept a conclusion by making them feel strong emotion, typically pity or fear.

False Cause: Mistakenly assuming that because one event followed another, or happened at the same time, the first event caused the second.

“Love is the most powerful feeling because it’s the strongest emotion in the world.”

“Let’s skip class and go down to the beach. Come on, everyone else is doing it.”

“You want to know what I think about your new boyfriend? I think the Packers are going to win the Super Bowl this year.”

“You can’t tell me how to be a good person. You are a proven liar and cheater.”

“I know gun rights supporters are concerned about the number of good jobs that the gun industry provides, but the economy will adapt to a gun-free society and provide lots of even better jobs.”

“Kim Kardashian says green grapes are the healthiest fruit so you should add them to your diet.”

“You either support university athletics or you hate the university.”

“Soccer is the toughest sport. No one has proven otherwise.”

“If we allow same-sex marriage, soon we will have to allow people to marry siblings, pets, and inanimate objects.”

“Former Congressman Anthony Weiner got caught sexting again—all politicians are crazy!”

“I don’t think those who sign up for Army Reserve should be forced into combat. I lost both of my sons in Iraq because of that.”

“Restricting access to handguns is like restricting access to automobiles—they both lead to thousands of deaths a year.”

“What do I think about Trump’s performance as President? I think he’s a deplorable human being!”

“Everyone knows English majors are the smartest students.”

“Most students may need to revise their papers to earn a good grade, but I don’t have to.”

“So, how often do you lie to your parents?”

“In the summer, ice cream sales go up and so do violent crime rates. Therefore, ice cream must make people more violent.”

“Whenever I don’t study, I get bad grades. God must be punishing me for something.”

Exercise 14: Peer Review/Grading Rubric for Assignment 3

As with Assignment 2, students need to bring 4 copies of their draft for Peer Review. I follow the same process as the last time. If the groups worked well the last time, I’ll let them stay in those groups, but if not, I’ll have them form new groups.

Here is the Peer Review sheet (again, also the Grading Rubric–which is important to share with students before they submit their papers for grading):

Is there a clear “thesis statement” that identifies the subtopics that will be discussed and previews the organization of the letter?

Does the letter stay focused on explaining the writer’s experiences and observations as they relate to self-reliance and conformity is society today?

Is the letter well organized? Are paragraphs appropriate lengths and do they focus on different subtopics? Are transitions between paragraphs (and ideas) smooth?

Has the writer provided enough explanation and background information so the reader (Emerson) will not be confused and/or left with questions such as: Who? What? Where? Why? When? How? (make a note of sections where the writer needs to provide more explanation and/or background information)

Does the letter develop ideas with enough detail and examples so it is clear how the writer and/or others the writer has observed in modern society are or are not being self-reliant (and how this is affecting them for better or worse)?

Rate the letter’s grammar, clarity, and readability:

Needs improvement (lots of mistakes and confusing sentences

Developing (readable, but needs substantial improvements

Proficient (only minor revisions needed)

Advanced (a pleasure to read and I couldn’t find any errors)

Does this letter have a conclusion that sums up the main points, restates the thesis statement, and leaves a lasting impression?

Was this letter engaging (that is, did it hold your interest as you read it)? Why or why not?

Was this letter interesting and memorable (that is, does it go beyond the obvious and did you learn new things about either “Self-Reliance” or the way people think and act in society today)? Did the ideas expressed in the letter make some kind of lasting impression? Why or why not?

Other comments & suggestions:

All right, that’s it for now. I”ll update likely twice more during the semester to share all 15 weeks of fun.